Pain can often cloud your judgment, especially under extreme duress, but not for Air Force Col. William A. Jones III. As a pilot in Vietnam, he remained in control of his charred plane long enough to fly nearly 90 miles to relay information that would help save another pilot’s life. For his valiant effort, despite his many injuries, he earned the Medal of Honor.

Jones was born May 31, 1922, in Norfolk, Virginia. He grew up in the town of Warsaw before his family moved to Charlottesville at age 7. Jones’ mom was a teacher, his dad was an attorney and his grandfather, the senior William Jones, had been a U.S. representative who authored the bill that granted independence to the Philippines.

Jones finished high school early and went to the University of Virginia, where he graduated at age 19 with a degree in Spanish. From there, he entered the U.S. Military Academy in 1942. At West Point, he was known to be determined, confident and a scholar who competed on the school’s fencing team.

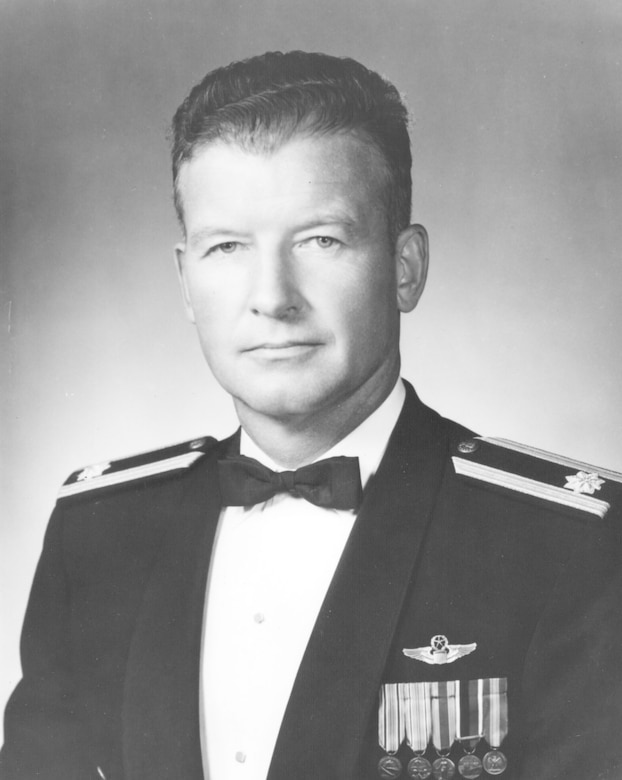

Jones was commissioned into the Army Air Corps in 1945, eventually transitioning to the Air Force when it became its own service in 1947. Within the first few years of his piloting career, he met and married Lois McGregor, and they had three daughters.

Jones hopped duty stations for several years, including a stint in the Philippines in the late 1940s. He went to the Air War College in Alabama and received his master’s degree in international affairs in 1965 before switching to an administrative role. But he longed to return to the air, so as a lieutenant colonel, he was sent to Vietnam to command the 602nd Special Operations Squadron. The air commandos were operating out of Nakhon Phanom Royal Thai Air Base in Thailand.

On Sept. 1, 1968, Jones led a flight of four propeller-driven A-1H Skyraider aircraft to escort two helicopters sent to rescue Capt. Jack Wilson, the pilot of an F-4 Phantom that went down near Dong Hoi, North Vietnam. Wilson successfully ejected but landed near a well-defended enemy supply road.

During the rescue mission, Jones’ aircraft was repeatedly hit by heavy antiaircraft fire as he made low passes over the ground to search for Wilson. One hit filled his cockpit with smoke, but he kept looking for the downed pilot.

Jones soon saw Wilson near a giant vertical rock formation. However, rescuers couldn’t get to him because enemy gunners at the top of the rock were firing at Jones, who couldn’t fire back for fear that he would hit Wilson. Once another crew told Wilson to move locations and had confirmation that he’d done so, Jones went back and fired on the enemy gunners with cannon and rocket fire. However, on his second pass, Jones’ aircraft was hit several times.

One round struck the ejection mechanism right behind Jones’ headrest, igniting the system’s rocket that propels the pilot upward. Flames erupted in the plane’s central fuselage and engulfed the cockpit. To survive, Jones set off the system to jettison the canopy. According to his Medal of Honor citation, ”the influx of fresh air made the fire burn with greater intensity for a few moments, but since the rocket motor had already burned, the extraction system did not pull Col. Jones from the aircraft.”

A retelling of the incident in a 2014 edition of the Air Commando Journal said that Jones’ oxygen mask was burned beyond use and that his helmet visor and the gauges and knobs on his instrument panel had melted. Jones himself suffered burns all over his body.

Miraculously, the plane was still able to fly. Even though Jones was in searing pain, he managed to get the aircraft to climb. He tried to let the other aircraft know where Wilson and the enemy gunners were, but his transmissions were blocked by the other pilots’ calls to him to bail out. Quickly, most of Jones’ transmitters stopped working. He was left with only one receiving channel and no way to communicate.

Jones decided his best option was to fly the still-operable aircraft to his home base so he could pass on the vital information about Wilson’s whereabouts. He used hand signals to let his wingman know what he was doing. That wingman then helped direct him back to their base about 40 minutes away.

Once Jones landed the damaged aircraft, he refused medical help until he was able to relay the information about the downed pilot. Thanks to his courageous efforts, Wilson was rescued later that day.

Jones was transferred to Japan and then Brooks Army Hospital at Fort Sam Houston, Texas, where he received extensive treatment for his burns. When he fully recovered, he requested to return to his combat tour. While his flying status was returned to him, he was instead assigned command of the 1st Flying Training Squadron at Andrews Air Force Base, Maryland, where he was promoted to colonel in November 1969.

Tragically – after surviving all of that – Jones died 15 days later on Nov. 15, 1969. According to the Danville, Virginia, newspaper called The Bee, Jones was flying his personal aircraft, a single-engine Piper Pacer, when it clipped a power line and crashed near the Woodbridge Airport in Virginia. A final cause of the crash was never determined, but investigators said they believed he suffered some sort of medical issue midair.

Jones, who had flown 98 combat missions in Vietnam, was 47.

According to the Air Commando Journal, the approval for Jones’ Medal of Honor came one day before his death and that he had been made aware of it. The West Point Association of Graduates later said Jones considered the award a tribute to all of the rescue pilots from his squadron.

On Aug. 6, 1970, President Richard M. Nixon presented the medal to Jones’ widow in front of his entire family during a White House ceremony. Jones’ youngest daughter, Mary Lee, gave the president a copy of a book her dad had written called ”Maxims for Men-at Arms: A Collection of Quotations by the Great and the Humble.” The first copy had been delivered to Jones the day before his death.

Jones was buried at St. John’s Church Cemetery in his hometown, right next to his father and grandfather.

Several military facilities have been named in Jones’ honor over the decades, including a new state-of-the-art Air Force facility that opened in 2011 at Joint Base Andrews. The West Point Association of Graduates may have summed up Jones life best: ”A true patriot, his life stands as a model for those who would achieve success based on courage, integrity, dedication, and plain old diligence.”