Heroes are often people who volunteer for missions they know might be their last. During the Vietnam War, despite having reached retirement age while managing to survive two wars, Army Capt. Ed Freeman volunteered for just such a mission.

Freeman was born on Nov. 20, 1927, into a big family who lived on a farm in Hattiesburg, Mississippi. He never finished high school. He later said he just wanted to get out of his hometown, so in 1944, he joined the Navy and served on an oiler that provided petroleum to combat ships in the Pacific during World War II.

He went back to finish school after the war ended, then enlisted in the Army, where he served in Korea and received a battlefield commission in 1953.

Freeman’s tour in Korea made him want to be a pilot, so as soon as he returned to the states, he applied for flight school. At first he didn’t qualify because at 6 feet, 4 inches, he was too tall. But he eventually got in and became a pilot. For the next decade, he flew around the world mapping countries, first in fixed-wing aircraft before switching to helicopters.

Vietnam

Freeman was close to retirement when war broke out in Vietnam. He was an experienced pilot by then and assigned to the 229th Assault Helicopter Battalion, which was sent to deliver troops to what became known as the Battle of Ia Drang, the first major battle between the United States and North Vietnamese troops.

Freeman was the flight leader and second-in-command of a 16-helicopter lift unit on Nov. 14, 1965, when he and his men were tasked with dropping infantrymen from the 1st Battalion, 7th Cavalry Regiment, into a remote landing zone beside the Ia Drang River along the Cambodian border.

Everything seemed to be running routinely until the fifth drop, when a heavily armed enemy force opened fire. The attack was so intense that once Freeman’s crew got back to the staging area, all helicopter operations into the landing zone were shut down.

But the men on the ground were struggling to maintain their defenses. They were taking on heavy casualties and running low on ammunition and supplies.

Back at the staging area, the commanding officer, Army Maj. Bruce Crandall, called for a volunteer to fly back in with him to help. Freeman was the only one who raised his hand. For him, it wasn’t an option.

“I put ’em in there,” Freeman explained in a Library of Congress interview.

So, for hours on end, Freeman and Crandall flew unarmed helicopters — many of which had to be switched out due to damages — into the hot zone to deliver critically needed ammunition, water and medical supplies for the soldiers.

Their mission became that of evacuators, too, when medical helicopters refused to fly in. Fourteen times, Freeman and Crandall flew to a small emergency landing zone within 200 meters of the enemy to evacuate dozens of seriously wounded soldiers.

“I put in 14-and-a-half hours that day, in and out of that LZ, doing that. And at 10:30 [p.m.], I made the last landing with some guy holding a flashlight and hauling those people out,” Freeman remembered.

The Battle of Ia Drang inspired the critically acclaimed book “We Were Soldiers Once … And Young,” which was turned into a similarly titled movie, “We Were Soldiers,” in 2002.

A Long Time Coming

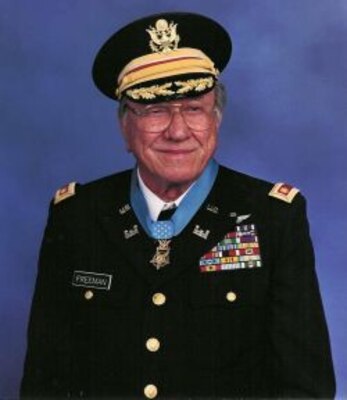

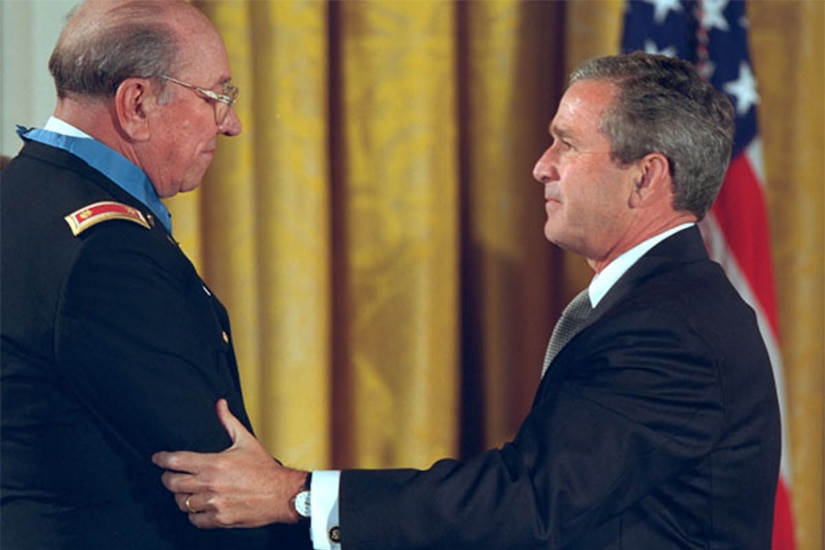

Freeman was initially awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross, but after decades of work by men with whom he served, including Crandall, it was eventually upgraded. He received the Medal of Honor on July 16, 2001, from President George W. Bush.

Bush summarized Freeman’s actions, saying, “The man at the controls flew through the gunfire not once, not 10 times, but at least 21 times. That single helicopter brought the water, ammunition and supplies that saved many lives on the ground. And the same pilot flew more than 70 wounded soldiers to safety.”

Freeman retired as a major in 1967 after 23 years of service. He moved to Boise, Idaho, where he raised his family and flew helicopters for the Interior Department for 20 years.

He died in 2008 at age 80 due to complications from Parkinson’s disease. He was buried with full military honors in the Idaho State Veterans Cemetery.

The post office in Freeman’s Mississippi hometown was named for him in 2009.

Meanwhile, Crandall, who flew the gallant mission with Freeman, was at the White House ceremony when Freeman was given the Medal of Honor. Crandall went on to receive his own Medal of Honor in 2007.