This week we’re honoring not one, but five Civil War sailors who helped free their grounded warship during the Battle of Charleston Harbor in South Carolina in 1863. Gunner’s Mate George Leland, Coxswain Thomas Irving, Seaman Horatio Young, Landsman William Williams and Landsman Frank Gile all played an integral role in the mission. For their efforts, they earned the newly created Medal of Honor.

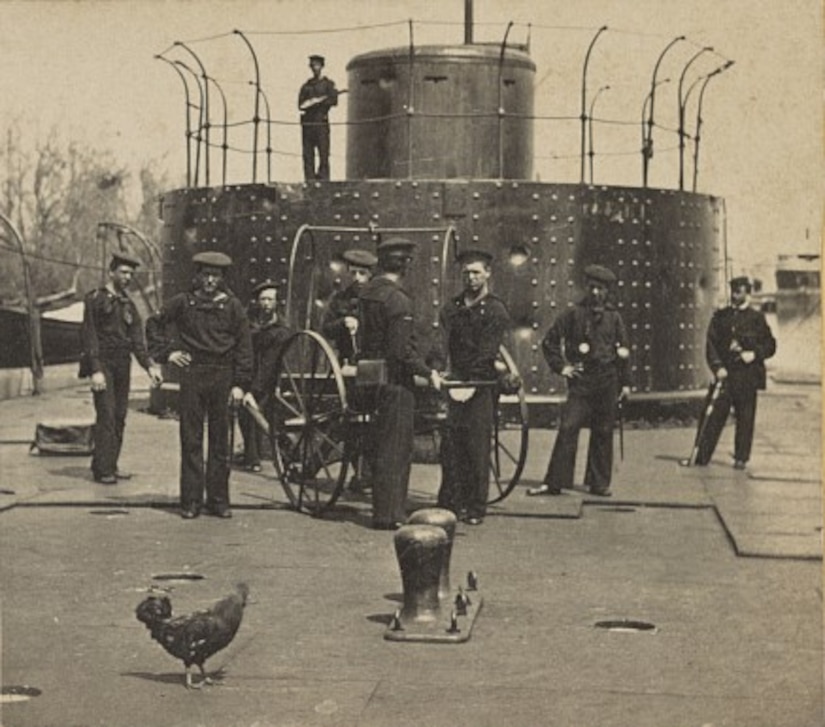

On Nov. 16, 1863, all five men were serving on the USS Lehigh, a Union monitor ship that came to the aid of soldiers on Morris Island, South Carolina. The soldiers were being fired on from long range by Confederate troops at Fort Moultrie on Sullivan’s Island near Charleston, South Carolina.

The Lehigh and other ironclad ships in the area were ordered to cover approaches to the Union position from the water in case the Confederates intended to launch a boat attack.

The Lehigh’s commander ordered its crew to anchor the ship by sundown, but flood tides that night moved the ship and grounded it on a sandbar. The movement also put the ship within range of Confederate guns. The enemy realized this change in circumstance at daybreak, so several of their batteries started blasting the ship from 2,300 yards away.

The Lehigh was a sitting duck. Hundreds of rounds hit the ironclad, including six that broke through the deck’s armor. One strike to the hull started a leak that let in nine inches of water per hour.

Two other ironclads, the Nahant and the Montauk, came to the Lehigh’s rescue to try to tow it off the sandbar.

Leland, a Savannah, Georgia, native; and Irving, a young man who had immigrated to New York from England, were tasked with taking a small boat to the Nahant to pass a line over to begin the towing process. Navy assistant surgeon William Longshaw went with them.

Leland and Irving rowed as cannon and mortar shells whizzed past them; meanwhile, Longshaw carried and handed to the Nahant’s crew members the lines of the thick ropes, known as hawsers, that would be used to tow the ship. They twice succeeded in passing the hawsers under heavy fire, but both times, enemy guns cut the lines.

Eventually, casualties were reported on the Lehigh, so Longshaw had to go to the aid of the wounded. That’s when three more sailors stepped up to make a third attempt: Young, an 18-year-old from Calais, Maine; Williams, an Irishman living in Pennsylvania; and Gile, a 16-year-old from North Andover, Massachusetts.

This attempt succeeded. Within about an hour, the line the men took to the Nahant pulled the Lehigh off the sandbar, getting it out of its precarious position.

Seven men on the Lehigh were wounded during the assault. That number likely would have been much higher if it weren’t for the brave efforts of the five men who secured the ship’s move to freedom.

Leland, Irving, Young, Williams and Gile were all praised for their courage and each received the Medal of Honor, as well as a promotion to the next rate.

Unfortunately, Longshaw wasn’t eligible for the high honor because of his status as a medical officer. Enlisted sailors were the only men who could receive the award until 1915 when officers became eligible, too.

It didn’t take long for the Lehigh to recover. It was repaired and returned to action by January 1864.

As for its five saviors? Leland moved to Maine after the war and lived until March 1880. Young returned to the St. Croix Valley in Maine and lived until 1913. Williams returned to life in Philadelphia; he died in May 1893. It’s unclear what Irving did after the war or when he died.

Gile, the youngest of the men, remained in the Navy and served on three other ships. He joined the Army after the war ended, according to his hometown newspaper, the Eagle Tribune, and died in his hometown in March 1898.