Army Air Corps 1st Lt. Jack Mathis gave his life to make sure one of the biggest bombing campaigns on the Western Front of World War II was successful. He earned the Medal of Honor for his actions; however, his story really can’t be told without including his older brother, Mark, who served at the same time and whose wartime journey is inextricably linked.

Jack was born Sept. 25, 1921, in Sterling City, Texas, to parents Rhude Mark and Avis. He had two brothers; Mark, who was older, and younger brother Harold.

Jack graduated from San Angelo High School. According to the book, “Assignment to Hell,” he enrolled in San Angelo Business College before deciding to enlist in the Army on June 12, 1940. After serving for a few months at Fort Sill, Oklahoma, Jack learned that Mark, who had also enlisted, had transferred to the Army Air Corps. Jack followed suit, and they both began training as bombardiers in the same unit.

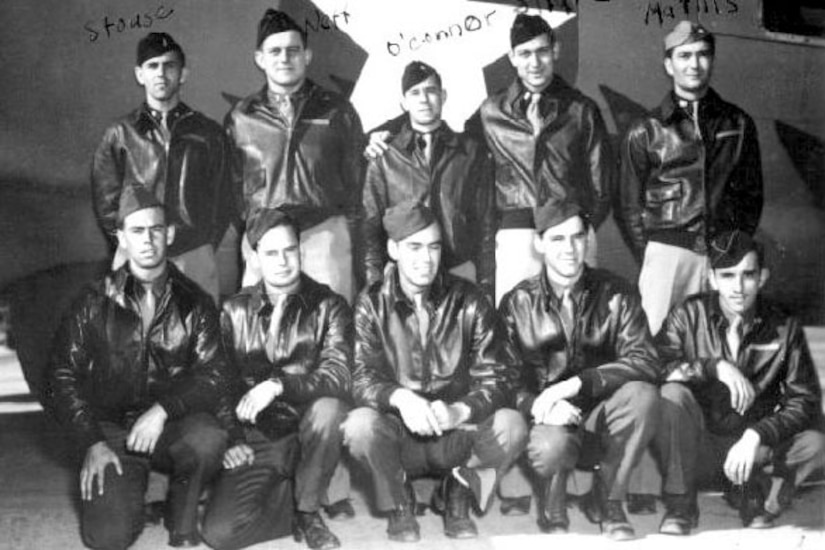

The younger Mathis was commissioned as a second lieutenant on July 4, 1942. About two months later, he was sent to England to serve with the 8th Air Force as a bombardier for the 303rd Bomb Group’s 359th Bomb Squadron. Mark was sent elsewhere.

Reconnecting

As 1942 turned to 1943, the U.S. Army Air Forces had begun a daytime strategic bombardment plan meant to cripple the German war effort. High on the priority list: Destroying submarine production.

In mid-March, Mark was transferred from the North Africa campaign to a unit in England. Upon arrival, he got to stop by Jack’s base to see him the night before a raid on the submarine marshalling yards at Vegesack, Germany. Jack, now a 1st lieutenant, was the lead bombardier for the 100-plane mission.

In a later radio broadcast, Mark said his brother wanted him to join his crew on their B-17, called The Duchess, for the raid, but it couldn’t be arranged. Instead, Mark watched The Duchess fly off without him on March 18, 1943. It was the last time he saw his brother alive.

Determination and Tragedy

As lead bombardier on the mission, Jack’s accuracy was crucial — if his aim was off, the bombers following him would also be off-target.

The crew of the Duchess initially encountered enemy fighter aircraft on the way to the target. Jack’s friend and fellow navigator, 1st Lt. Jesse H. Elliott, recalled that Jack had run out of ammunition at least twice because he had to pass him more throughout the flight.

The bomber had just started its first bomb run when intense anti aircraft fire exploded all around them. Jack, however, stayed focused. He opened the bomb bay doors and was seconds from dropping his bombs on the target 24,000 feet below when The Duchess was hit right across the nose. Jack was knocked about 9 feet to the back of the compartment. The explosion tore a large wound into his side and abdomen and shattered his right arm, nearly severing it above the elbow.

The bombardier was in terrible shape, but he knew the mission’s success depended on him. So — likely through sheer determination and willpower — he dragged himself back to his Norden bombsight and released the bombs.

According to a September 1943 Fort Worth Star-Telegram article, Jack’s crew was accustomed to hearing a celebratory “bombs away!” from him during missions. This time, they only heard a faint, “bombs….” before the intercom went silent.

Jack died on top of his equipment, using his last act of strength to hit the switch to close the bomb bay.

“I still think that when Jack reached for the handle to close the bomb bay door, he already was dead — that even in death he still was carrying out his job, even though then only by reflex,” Elliott said during a March 1943 interview with future famed journalist Walter Cronkite.

Thanks to Jack’s dying actions, all of the other planes in his bombardment squadron dropped their bombs directly on the target, making the attack a huge success.

But for the 26-year-old Mark, the mission’s results were devastating. The older Mathis watched as the damaged bomber carrying his brother’s body landed. That night, he asked to be transferred to the 359th Squadron to take over where his hero brother left off. The transfer was approved. Mark finished out the Duchess’ tour of duty with a different crew, then stayed on in combat in a different B-17.

Sadly, on May 14, 1943 — just two months after his brother’s passing — Mark’s bomber was shot down over the North Sea near Kiel, Germany. He was never heard from again, and his remains were never recovered.

Honors

Jack Mathis, who was only 21 when he died, had flown 14 missions in his short career. He was the only crewmember of The Duchess to die during its 59 missions.

Years later, reconnaissance photographs showed that seven enemy submarines and a majority of the shipyard they targeted during his 1943 mission had been destroyed. It turned out to be one of the most successful raids of the war in Europe.

Jack’s body was returned home and buried in Fairmount Cemetery in San Angelo, Texas. On Sept. 21, 1943, a ceremony was held at Goodfellow Field in San Angelo. On her middle son’s behalf, Avis Mathis received the Medal of Honor, as well as an Air Medal and Oak Leaf Cluster that Jack had earned on prior missions.

Jack’s Medal of Honor was the first awarded to an 8th Air Force airman. It is currently kept at the National Museum of the U.S. Air Force at Wright-Patterson Air Force Base in Ohio.

Mark also received accolades for his sacrifice, posthumously receiving the Air Medal and the Purple Heart. He is memorialized at the American Cemetery in Margraten, Netherlands.

The memories of both Mathis brothers live on. In 1966, the fitness center at Goodfellow Air Force Base was named for Jack. About two decades later, the municipal airport in San Angelo was renamed to honor both of the Mathis brothers.