Army Command Sgt. Maj. Gary Littrell’s more than two decades in service can likely be summed up by his leadership during a precarious situation in Vietnam, where he earned the Medal of Honor. The skilled Ranger was advising a small battalion of soldiers hen they got trapped on a hillside by an enemy 10 times their size.

Littrell was born Oct. 26, 1944, in Henderson, Kentucky. His mother died when he was 5, and his dad wasn’t around, so he ended up moving in with his grandparents on their farm.

When he was 9, Littrell’s uncle drove him about 90 miles to Fort Campbell, Kentucky, to watch as soldiers demonstrated parachute jumps. Then and there, the young Kentuckian decided he wanted to be one of them. So, in 1961, one day after his 17th birthday, he joined the Army.

Littrell was deployed in 1962 to Okinawa to join the newly converted 173rd Airborne Brigade. While he was there, he married a local woman named Mitsue. They had two boys.

In 1965, Littrell was reassigned to the 82nd Airborne and sent back to the U.S. two days before the 173rd was ordered to Vietnam. Instead, he deployed with the 82nd to the Dominican Republic before returning home to attend Ranger School, graduating in 1966. Littrell remained an instructor there until 1969, when his orders to Vietnam came through.

About eight months into deployment, then-Sgt. 1st Class Littrell was working as an adviser to the 23rd Vietnamese Ranger Battalion at Dak Seang, a base camp in central Vietnam near the Laotian border.

On April 4, 1970, the unit moved south toward the Cambodian border to search out enemy fighters and call in airstrikes against them. That night, when they reached the top of a hill, they realized they were surrounded by about 5,000 North Vietnamese troops. Littrell’s unit, made up of 473 South Vietnamese and three other American advisers, was vastly outnumbered.

As soon as they set up a defensive perimeter, the enemy released a barrage of mortar fire that killed the unit’s South Vietnamese commander and one American adviser. The other two advisers were seriously injured.

Littrell, 25, was the only American left to fight. Thankfully, he’d learned to speak Vietnamese at the Defense Language Institute before deployment, so he was able to communicate with the remaining men.

Over the next four days, Littrell and the 23rd Battalion fought for their lives. According to his Medal of Honor citation, he showed “near superhuman strength” by repeatedly going into the line of fire to direct artillery and call in air support during the day. At night, he did the same to mark the unit’s location. His bravery, leadership and will to keep pushing inspired the men with him to continue to resist.

“My primary job was just command and control, trying to get the Vietnamese to stand and fight, but I was on the radio probably more than anything,” Littrell said in a Veterans History Project interview.

The battalion pushed back assault after assault as Littrell continued to move to the most perilous points to redistribute ammunition, strengthen some of the lines that were faltering, care for the wounded and continue encouraging his men to keep fighting.

Littrell said the ordeal and lack of sleep was so exhausting that much of what happened to him was hazy for a long time.

“When … our missions were declassified, a young historian went to the Pentagon and got the actual operations report and some of the witness statements for my award,” Littrell said. “I started reading them, and it came back: ‘Oh my God, I do remember that happening.’ It was, of course, some interesting reading, but … you get so fatigued that you just, you don’t remember everything that went on. You just remember you had your hands full.”

On their last day stuck on the hill, Littrell’s commander radioed to say troops had cleared a small path for the trapped battalion to try to escape. The journey led them through several ambushes that they managed to stave off with the help of helicopter gunships protecting their flanks. Littrell repeatedly kept order amid the chaos and directed airstrikes on the enemy, some of which came within 50 meters of his own position.

Five treacherous miles later, they made it back to friendly forces. Littrell later learned that, of the 476 men he started the mission with, only 41 came back alive. However, thanks to his courage and leadership, many lives were saved.

Not long after the ordeal, Littrell said he was told his name had been put in for consideration for the Medal of Honor. But when several months went by and no update came, he forgot about it.

More than three years later, Littrell was called into the office of the 101st Airborne’s commanding general.

“Back then, I was a little wild and pulled some crazy things every now and then,” Littrell said. “[So] the first thing that went through my mind was, ‘Oh, my God, what the hell did I do now?'”

He’d done nothing wrong. The general wanted to pass on the news that his Medal of Honor nomination had been approved. On Oct. 15, 1973, Littrell received the nation’s highest honor from President Richard M. Nixon during a White House ceremony.

Littrell has always maintained he’s only a conduit for the medal’s true owners.

“I’m wearing this medal for the 400 and some people that died those four days,” he said during an interview. “I’m their representative. They won this medal. I was selected to wear it for them.”

Littrell continued his career in the military until retiring from service in October 1983. He even deployed a second time to Vietnam in 1974. His service there, though, was something he rarely talked about even to his own kids, who went on to serve in the Air Force.

Littrell moved to Florida in 1987 and worked for many years counseling veterans at the Department of Veterans Affairs. In 1993, he was inducted into the Army Ranger Hall of Fame.

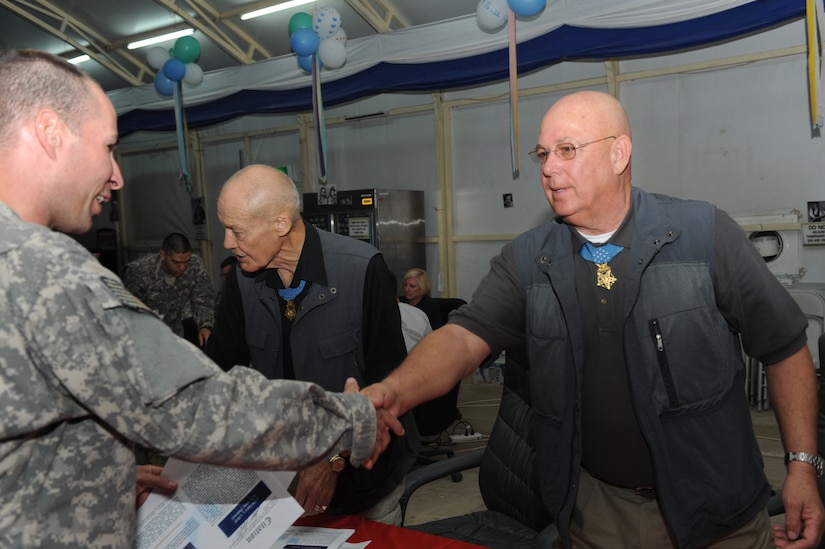

It took Littrell about two decades to talk more about his experiences, which he has often done with schoolchildren and groups in his community. In the early 2000’s, Littrell and fellow Medal of Honor recipient Robert Howard, a retired colonel who also served in Vietnam, traveled several times to Camp Liberty in Iraq to support deployed soldiers. During that time, Littrell also served as the president of the Congressional Medal of Honor Society.

Littrell and his wife live in St. Pete Beach, Florida. In 2015, a bridge in the city was renamed and dedicated in his honor.