Actions worthy of the Medal of Honor don’t always come from a compilation of courageous deeds; they can happen in the shortest window of time. That was likely the case for Navy Petty Officer 2nd Class William Halyburton Jr., a corpsman who died on his first day in combat toward the end of World War II.

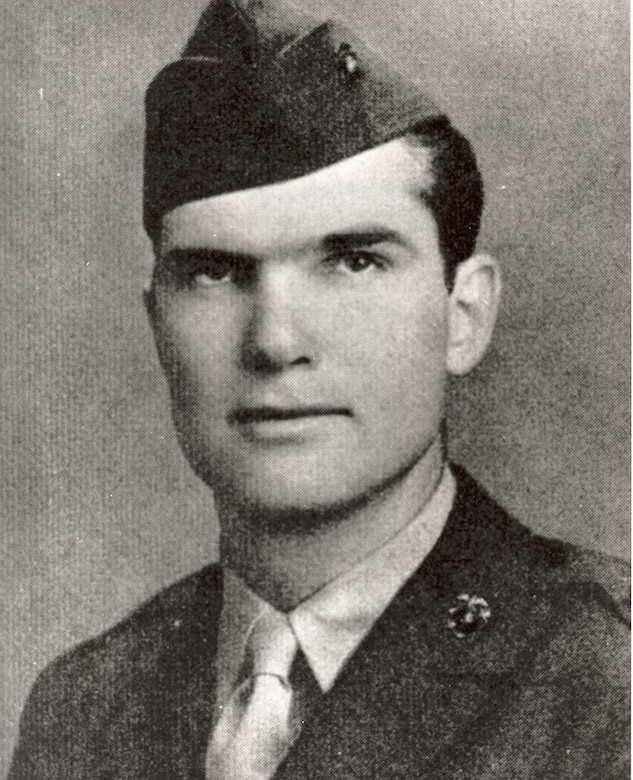

Halyburton was born on Aug. 2, 1924, in Canton, North Carolina, to parents Mae and William Halyburton. He had two brothers, Bob and Joe. In 1940, the family moved to Miami, but Halyburton only stayed for a short while before moving back to North Carolina to live with his aunt and uncle in Wilmington, according to newspaper reports from the 1940s.

Halyburton played sports and was a devout Christian during his time at New Hanover High School, from which he graduated in 1943. He entered seminary at Davidson College in Davidson, North Carolina; however, those plans had to be put on hold when he was drafted to serve in World War II.

According to a 2010 Asheville Citizen-Times article, Halyburton was a conscientious objector, meaning he would serve but would not bear arms. So, in August 1943, he was allowed to choose the Naval Reserve, where he joined the hospital corps and spent more than a year in training.

By January 1945, Halyburton had reached the rank of pharmacist’s mate 2nd class and was sent overseas as a medic for the 2nd Battalion, 5th Marines, 1st Marine Division. The division had pushed its way across the Pacific and was preparing to battle for Okinawa, an island near Japan’s home shores.

On May 10, 1945 — Halyburton’s first day in combat, according to his mother — the 1st Marine Division was on the island and preparing to move across the Awacha Draw, a strategically important ravine that was heavily fortified by the Japanese. Americans dubbed it “Death Valley” since many soldiers and Marines fell as they tried to cross it.

Halyburton was serving with a rifle company that day, and he watched a lot of Marines fall. They weren’t able to be carried away to safety, so the wounded were treated where they fell or would have to be retrieved later.

Enemy fire on his unit was intense, but, as they crossed the draw, the young medic didn’t hesitate. He ran across the ravine, up a hill and into a fire-swept field where his company’s advance squad was pinned down. Despite a nonstop barrage of mortar, machine gun and sniper fire, Halyburton ran until he reached the furthest wounded Marine.

As he started to give that Marine aid, the wounded man was struck a second time by a Japanese bullet. Halyburton quickly put his own body between the wounded man and the line of fire, continuing to give aid until he was also gravely wounded. The 20-year-old collapsed and died while trying to save his comrade.

Halyburton’s outstanding devotion to duty amid such a terrifying situation led to his immediate nomination for the Medal of Honor. On May 8, 1946 — nearly a full year after he died — Halyburton’s family was presented the nation’s highest honor for valor on his behalf. During a ceremony at Bayfront Park in Miami, Navy Rear Adm. John F. Shafroth Jr. bestowed the medal to Halyburton’s brothers, who had also served in the Navy during the war.

Halyburton was buried at the National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific in Hawaii.

While he only spent one day in combat, his legacy has lived on. In 1984, the guided missile frigate USS Halyburton was commissioned in his honor. Several other military structures were also named for him, including Halyburton Naval Health Clinic in Cherry Point, North Carolina; a barracks at Naval Air Station Pensacola, Florida; and a road at Walter Reed National Military Medical Center.